First Discovery

The next reported find was in 1880 when Aboriginals brought topaz to the Parkers, the owners of Bangate Station. Mrs Parker, thinking they were diamonds, sent her brother, Ted Field, and a station hand named Hudson, to investigate the area around Lightning Ridge where she suspected the Aboriginals had found them. Discovering nothing as clear as the Aboriginals’ stones, but a number of other attractive stones.

It wasn’t until 1887, when a piece of opal was discovered in a gravel pit which is now part of the famous Nine Mile field, that it came to the notice of the Mines Department.

Initial Interest

However, the first interest shown in this opal was when Jack Murray, a boundary rider on Dunumbral Station, found a floater late in 1900 on the eastern side of the ridges while setting a rabbit trap for dog food. It wasn’t until 1901 that he sank the first shaft on Lightning Ridge.

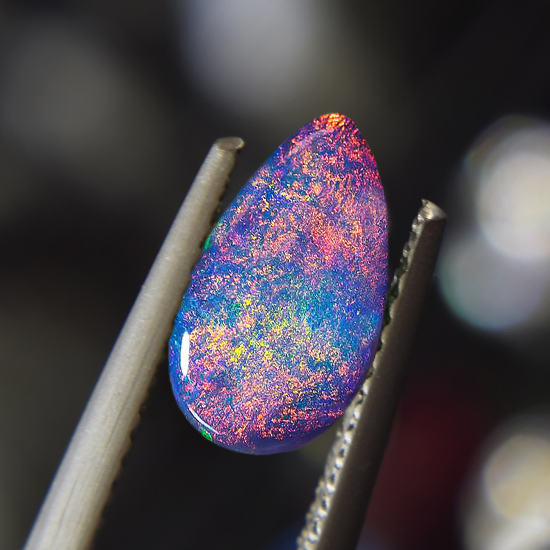

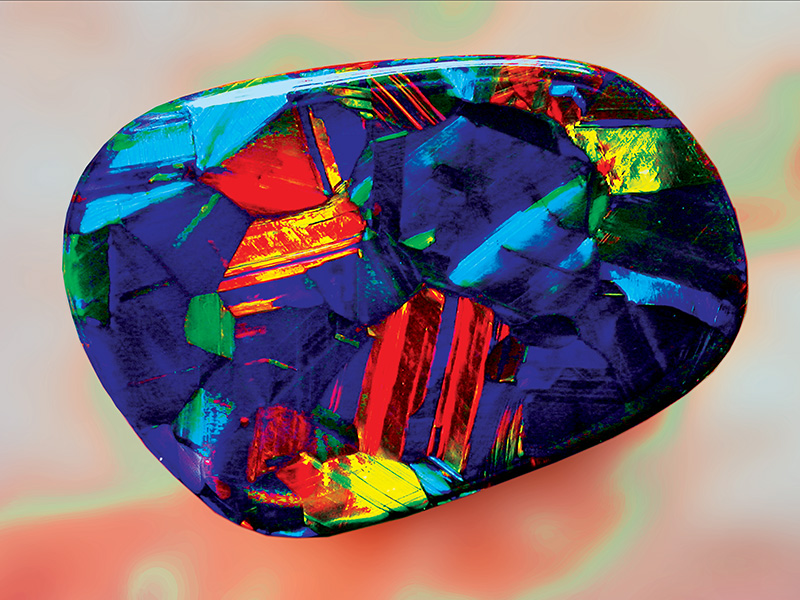

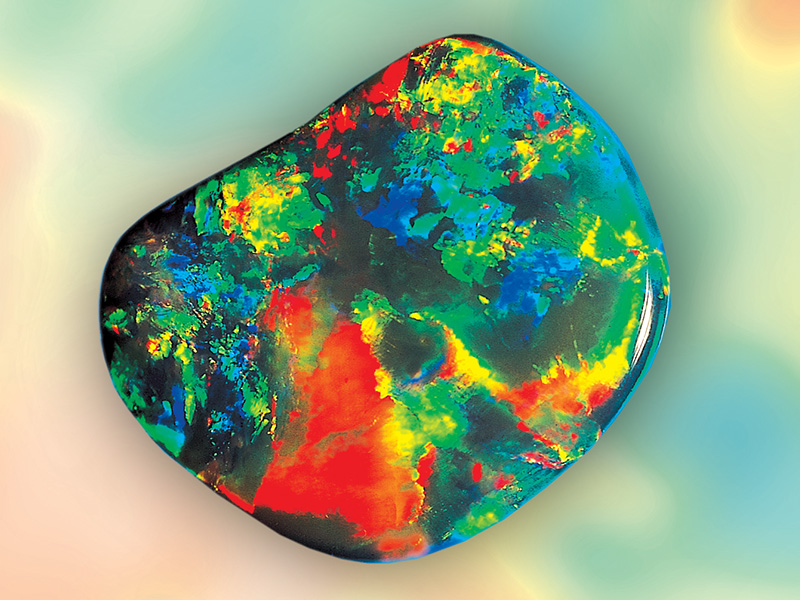

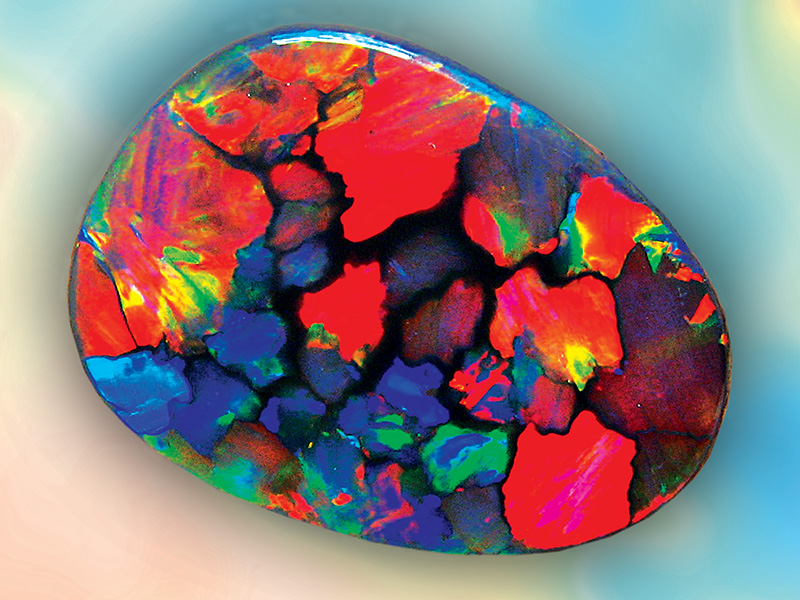

Lightning Ridge – to find a more appropriate name for the home of such a beautiful gem would be quite difficult, as the fields have no equal in the world.

The name, though unofficial, became well entrenched during the latter part of the 19th century, long before the discovery of opal.

Naming of Lightning Ridge

It’s unknown who originally called it Lightning Ridge, probably boundary riders from surrounding stations. It possibly came about after a terrifying electrical storm one night. Lightning killed a shepherd, his dog, and 600 sheep while sheltering on one of the ridges. The name Lightning Ridge has since flourished. Government departments used it for nearly 100 years before officially gazetting it on 5 September 1963.

The main street of the present town is named after the now-famous opal ridges. Aboriginal folklore called them Moorillas, hence the name Morilla Street. Aboriginals explain the ridges supernaturally, saying that Byamee, their God and culture hero created them as a highway for his convenience during flood time.

The first building to use Lightning Ridge was a small inn, built-in 1884 by T. J. Merry, on the Walgett Angledool road a few kilometers to the west of the present town. Lasting only six years and changing hands multiple times before being pulled down in 1890 by George Kirkpatrick and incorporated into his Exchange Hotel at Angledool.

Current State

Today, after 100 years of mining, Lightning Ridge is a fast-growing town with a great future, producing large amounts of fine quality black opals. The only known place on earth this world-famous type of black opal is found. Yet, in 1903 when Sydney’s gem merchants, shrewd as they were, saw the first black opals, they rejected them outright as a worthless form of matrix, thereby losing a fortune for themselves.

Beginning of Lightning Ridge

Miners from White Cliffs played a significant role in the opening up of Lightning Ridge. One such person was Charlie Nettleton, destined to stamp his name upon Australian opal history as a former gold miner from Mount Brown. Nettleton had been trying his luck at White Cliffs when he heard of gold on the Queensland border north of Walgett. Following the Darling River, he walked to Walgett during the height of the great 1902 drought before heading north to investigate the gold. On his way through, He camped with the Ryan family, boundary riders at Lightning Ridge for Angledool Station, whose hut was two kilometers west of the present town. It was here that Nettleton saw his first black opal.

A syndicate is born

In September 1902, Nettleton camped with the Ryans and was shown the strange but beautiful black opal. It is unknown if he met Murray on this occasion or changed his plans regarding the gold after reaching Joe Beckett’s Weetalibah Inn 30 kilometres north of Lightning Ridge. Beckett was the first to buy Lighting Ridge opal from the Murrays and recognize the possibilities of a new field. It wasn’t until he met with Nettleton, an experienced opal miner, that he organised a syndicate to test his theory.

Nettleton started his first shaft for the syndicate on the high country now known as McDonald’s Six Mile on 15 October 1902. It was a duffer, and early in 1903, he moved across to the shallow Nobby, where Murray and the others were getting good stones.

Lightning Ridges struggling start

Here, he produced a fine parcel of opal, which was sent by the syndicate to a well-known Sydney dealer, who was anything but impressed. In the words of Bob Bishop, “he said it was far too young, a worthless form of matrix, and offered them £10 for the lot.”

Expecting a large cheque, the syndicate were devastated and dissolved as a result. Leaving Nettleton without an income, just his share of the opal.

The syndicate consisted of seven local graziers and business people, including Nettleton and Beckett. The Manager was Ferris of Gerongern Station, now Bairnkine. Armitage, manager of Dunumbral, Mr. Langloh Parker, owner of Bangate Station, and his bookkeeper, Frank Doucutt, a storekeeper from Collarenebri. Except for Nettleton, all contributed £25 to the capital of the syndicate, from which Nettleton earned £5 per week. Until this point, the small number of miners, though not encouraged, were tolerated.

Influences of Palaeochannels

Tertiary palaeochannels (ancient river channels) are found on many opal fields and are considered a factor in opal genesis. They are generally coarse-grained sand bodies with good porosity that could have acted as channels or conduits for water movement. Hence silica movement and opal deposition in adjacent areas. Faulting or fault zones are associated with opal formation and are considered conduits for silica-rich groundwater.

The digital elevation model (DEM) of Lambina (Fig. 1 below) indicates the possibility of remnant channels trending east to west. Opal occurrences in the area extending from Lambina through to Todmorden Outstation and south to Eeavinna Hill and England Hill occur in ‘breakaway’ country of mesas and eroded plains that cut into the Early Cretaceous Bulldog Shale.

Indicative signs

Many known opal occurrences are associated with these mesas (topographic highs, shown in red); the interpreted palaeochannels are coloured white (Fig. 1).

The palaeochannels originally began as topographic lows – stream channels that were later silicified during the Tertiary and now remain as highs caused by a reversal in topography resulting from erosion of the softer surrounding Tertiary and weathered Cretaceous sediments since late Tertiary times.

Fig. 1

Potential Future Sources of Opal

Opal in northern South Australia is so widespread — several hundred kilometres north of Coober Pedy. Areas such as WINTINNA, ABMINGA and through to Mintabie opal field on EVERARD. There appears to be much potential ranging from England Hill (Townsend and Scott, 1981) in the south. Lambina (Flint, 1980) to the north, Todmorden to the east and Mintabie to the west. This area of at least 10,000km2 includes sporadic occurrences of opal adjacent to mesas and, more importantly, contains remnants of palaeochannels.

technological advancements

The interpretation of remote sensing data will assist in further discoveries of opal through DEM pseudocolour images of Coober Pedy, Andamooka, and now Lambina and its surroundings. Still, there is only a sprinkling of known opal occurrences in northern South Australia over a vast area of ‘breakaway’ landscape. Closer-spaced airborne surveys to produce more detailed DEM images in selected areas should assist in this exploration.

Acknowledgements

References

The author thanks the PIRSA Division of Minerals and Energy for assistance with the photographs generated from the Coober Pedy office and the provision of map images from PIRSA Spatial Information Services and Publishing Services.

For further information, contact Jack Townsend (Ph: 08 8297 4799, Email: townsend.jack@myaccess.com.au)

Barnes, L.C., Townsend, I.J., Robertson, R.S., and Scott, D.C.— 1992

Opal: South Australia’s Gemstone

South Australia Department of Mines and Energy.Handbook, 5.

Brown, G., Townsend, 1.J. and Endor, K.— 1993

Some Far Northern Opal Diggings in South Australia

Australian Gemmologist, 18(8):252-25.

Flint, D.J.— 1980

Lambina Opal Diggings.

South Australia Department of Mines and Energy. Report Book, 80/103.

Hiern, M.N.— 1967

Opal Deposits in Northern South Australia

Mining Review, Adelaide, 122:37-39.

Horton, D.— 2002

Australian Sedimentary Opal — Why Is Australia Unique?

Australian Gemmologist, 21(8):278-294.

Primary Industries and Resources South Australia— 1998

Lambina Native Title Agreement

MESA Journal, 11:28-29.

McCallum, W.S.— 1980

Vesuvius Opal Diggings

South Australia Department of Mines and Energy. Report Book, 80/38.

Townsend, 1.J. and Robertson, R.S.— 1980

Wallatinna Opal Diggings

South Australia Department of Mines and Energy. Report Book, 80/34.

Townsend, I.J. and Scott, D.C.— 1981

Sarda Bluff, Ouldburra Hill, and England Hill Opal Diggings

South Australia Department of Mines and Energy. Report Book, 81/17.

Townsend, I.J.— 1981

Discovery of Early Cretaceous Sediments at Mintabie Opal Field

South Australia Geological Survey. Quarterly Geological Notes, 77:8-15.

Townsend, I.J.— 1990

Mintabie Opal Field: Mining and Geology

South Australia Geological Survey. Quarterly Geological Notes, 117:8-15.